The recent detection of West Nile virus in UK mosquitoes marks a significant and alarming development, as reported by the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA). This is the first occasion that this virus has been found in mosquitoes within the United Kingdom. The UKHSA confirmed the discovery, stating that while the risk of transmission to the general public is currently assessed as “very low,” health professionals will be advised appropriately to remain vigilant.

West Nile virus, a virus that predominantly circulates in birds and is transmitted to humans through mosquito bites, can often lead to mild or negligible symptoms; however, approximately 20% of infected individuals may experience more severe reactions, including headaches, high fever, and skin rashes. Fortunately, the UKHSA has indicated that there is currently no evidence of ongoing virus circulation among birds or mosquitoes in the UK, which is a reassuring point for public health officials.

Historically, the UK has not seen locally transmitted cases of West Nile virus, although there have been a few travel-related occurrences, with seven reported instances since the year 2000 influencing public awareness and health protocols concerning the virus. The virus is endemic to several regions around the globe, particularly parts of South America and Europe, and its geographical spread has been expanding in recent years.

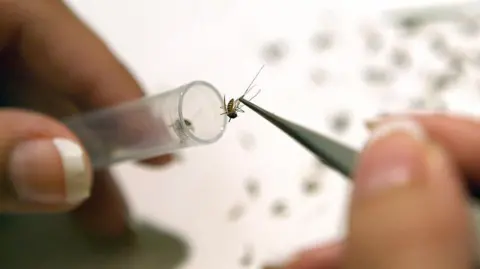

The fragments of the virus were identified in two samples of the *Aedes vexans* mosquito, a species recognized to inhabit the UK. This discovery emerged from a concerted research initiative led by the UKHSA in collaboration with the Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA), emphasizing the ongoing scrutiny in monitoring mosquito-borne diseases. Dr. Meera Chand, a deputy director at UKHSA, elucidated that although this is the first detection of the virus in UK mosquitoes, its presence is not unexpected considering the virus’s prevalence across Europe.

Dr. Arran Folly, who spearheaded the project responsible for the virus detection, also highlighted the pivotal impact of climate change, indicating that the changing environment is enabling mosquito-borne diseases to proliferate into new territories. He pointed out that while the *Aedes vexans* species is indigenous to the UK, rising temperatures may allow the introduction of non-native mosquito species, potentially increasing the risk of infectious diseases being transported into the region.

The concern regarding West Nile virus and its effects isn’t merely academic; it carries significant public health implications, especially as instances of related outbreaks have occurred elsewhere in Europe. For example, in Spain’s Seville, public protests erupted last year after five individuals succumbed to the effects of West Nile virus. This illustrates that the virus is not just a theoretical threat but has real-world consequences that local populations may face.

To counteract the risks associated with mosquitoes, experts recommend proactive measures against breeding habitats. Mosquitoes generally thrive in moist environments; therefore, eliminating standing water and adopting personal precautions, such as using mosquito repellent and constructing mosquito nets, play a crucial role in preventing the spread of insect-borne diseases.

In summary, while the detection of West Nile virus in the UK points to a new challenge for public health, it simultaneously signifies the importance of ongoing surveillance, community awareness, and potential proactive health measures to manage and mitigate any future impacts of mosquito-borne viral threats. The collaboration among health agencies and researchers will continue to be vital in navigating this evolving landscape of infectious diseases associated with changing environmental conditions.