Recent archaeological findings have highlighted a fascinating aspect of Roman-era entertainment right in England. In a remarkable excavation at Driffield Terrace, York, archaeologists have unveiled the skeleton of a man believed to have been a gladiator who faced off against wild animals such as lions. This significant discovery is heralded as the first solid evidence of gladiatorial combat involving animals, challenging previous understandings of Roman entertainment culture.

The remains of a man aged approximately 26 to 35 years at the time of his death were found with distinct bite marks on his pelvis, interpreted as likely caused by a lion. Dating back between 1,825 and 1,725 years, this skeleton was unearthed within a graveyard recognized as a gladiator burial site. The York Archaeological Trust led the effort to recover these remains, creating a surprising connection to the Roman Empire’s expansive reach and the nature of spectacles held beyond the grandeur of the famed Colosseum in Rome.

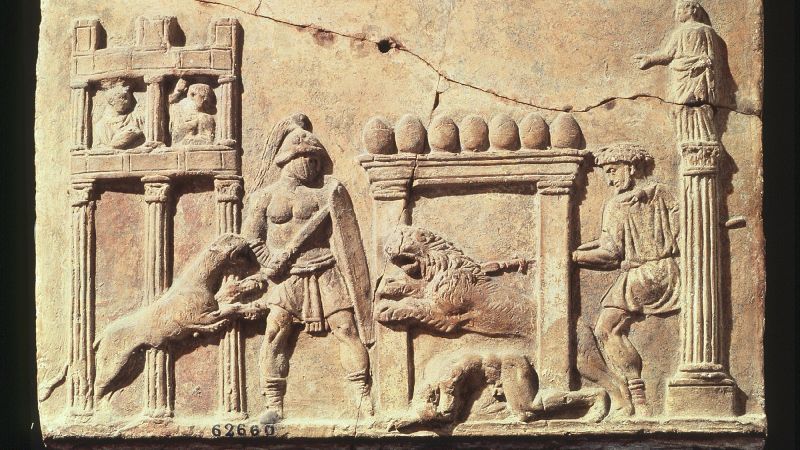

In 2010, the site gained attention when a documentary revealed the discovery of 82 skeletons of able-bodied young men, contributing to its designation as a gladiator graveyard. The importance of this new skeletal find lies in its potential to reshape our perception of the violent spectacles for which the Roman Empire was known. As noted by Tim Thompson, the lead study author and professor at Maynooth University, our historical contexts have largely depended on texts and artworks. This skeleton acts as physical evidence affirming that such spectacles occurred and provides insight into Roman entertainment practices, even in regions far from Rome.

The way Romans managed their dead during this period—cremation or burial along major roads rather than within settlements—offers further complexity to our understanding of their social structures. The discovery at Driffield Terrace began with construction activity in 2004 that unveiled this cemetery, revealing an unusual collection of injuries and burial practices, such as decapitation, which hints at the turbulent lives led by these men.

When researchers scrutinized the unique marks on the pelvis of one skeleton, they employed advanced 3D scans to make comparisons with known carnivore bite patterns. This investigation affirmed the bite marks belonged to a large cat—likely a lion—providing direct evidence that gladiators did indeed engage in combat with such animals, effectively confirming an element of gladiatorial culture hitherto well-documented but not substantiated through direct evidence.

Past academic renditions emphasized visual representations, artwork, and textual evidence, which could not definitively establish that such brutal contests occurred in areas outside of Rome’s core. As Kathleen M. Coleman from Harvard University reflects, while artistic interpretations depict these events, it is the physical evidence from this skeleton that marks a significant advancement in our historical insight into such brutal human-animal interactions.

Additional analyses revealed the man experienced several health issues, possibly stemming from childhood malnutrition, along with signs of strenuous physical work that further point to his role as a beast-fighting gladiator, termed a “bestarius.” Contrary to earlier notions of gladiators strictly as slaves or soldiers, this discovery allows for an enriched understanding of their social landscape and motivations, emphasizing that some gladiators could achieve fame and potentially earn their freedom.

With this groundbreaking find, scholars are now better equipped to conceptualize the perilous nature of gladiatorial life and the dynamics within arenas where human versus animal contests unfolded. The man’s death from an untreated lion bite, coupled with a subsequent decapitation—a potential act of mercy—illuminates not just his mortality but the cultural practices surrounding death and spectacle in the Roman world.

Overall, these findings paint a vivid picture of York’s integration into the Roman Empire, shedding light on how deeply theatrical and violent spectacles may have influenced social interaction and power dynamics between humans and nature. Future exhibitions, such as the Roman exhibit in York’s DIG: An Archaeological Adventure, are set to offer insights into these ancient customs, contributing to a broader narrative of gladiatorial practices across the empire.