In an intriguing turn of events, an object identified as Cosmos 482, a remnant from a Soviet space mission that failed more than half a century ago, is expected to reenter Earth’s atmosphere as early as this week. This surprising return has grabbed the attention of space enthusiasts and scientists alike, highlighting the ongoing legacy of space exploration and the challenges associated with space debris.

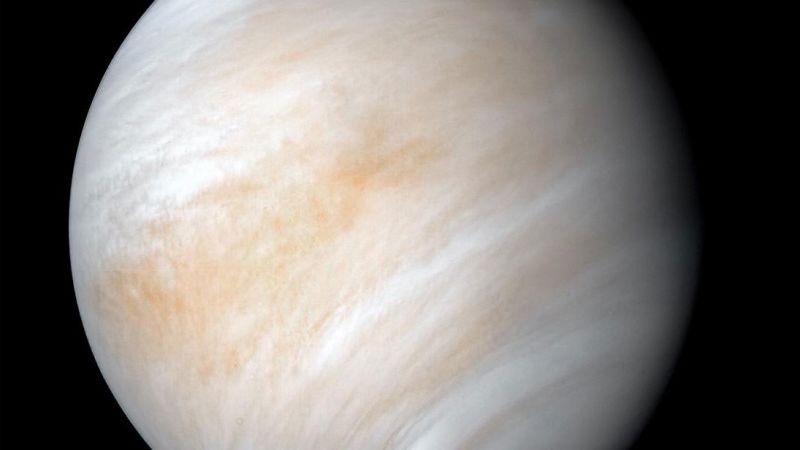

Cosmos 482, also referred to as Kosmos 482, remains an enigma; much about it is still unknown. Predictions project that it will make its atmospheric entry around May 10. However, given the uncertainties surrounding its shape, size, and the unpredictable nature of space weather, pinpointing its exact reentry trajectory has proven to be quite challenging. Experts are also uncertain about which component of the vehicle will fall back to Earth. Preliminary analyses suggest that it might be the probe or “entry capsule” designed to withstand the immense heat and pressure during its landing on Venus, where atmospheric conditions are significantly harsher than those on our planet.

Despite the potential for Cosmos 482 to survive its descent and impact, experts like Dr. Jonathan McDowell, an astrophysicist from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, emphasize that the risk to human life is minimal. He asserts that while there is no cause for major concern, a falling capsule might pose a small risk if it were to strike an individual directly. Historically, the reentry of space debris is a common occurrence, with most materials disintegrating in Earth’s atmosphere due to immense friction and pressure experienced at high speeds.

However, should Cosmos 482 be the Soviet reentry capsule many suspect, it boasts a significant heat shield, increasing its chances of surviving the fall intact. Dr. McDowell suggests that because of this, it could feasibly make it to the ground, reflecting a unique challenge in space debris management that persists to this day.

Delving into the history behind the spacecraft, the Soviet Space Research Institute (IKI) established its Venera program during the height of the space race in the mid-20th century, aimed at exploring Venus. Multiple probes were launched during this period, with some successfully transmitting data back to Earth before ceasing operations. Out of two specific missions launched around 1972, only one, V-71 No. 670, successfully transmitted information from the planet’s surface, highlighting the unpredictable nature of space missions.

The remnants of the ill-fated V-71 No. 671 spacecraft led to the formation of space debris, with Cosmos 482 likely being a part of this; researchers speculate it to be a cylindrical entry capsule based on its orbit behavior over several decades. This particular debris is categorized as “density-high,” given its ability to remain in low orbit without deteriorating for an extended period.

Nonetheless, an essential piece of advice comes from Marlon Sorge, an aerospace expert: should Cosmos 482 reach Earth’s surface, individuals must avoid attempting to touch it. This historical spacecraft could contain dangerous remnants, and thus, calling local authorities is imperative.

As discussions around this returning relic continue, the implications of space debris management remain significant, as emphasized by Parker Wishik from The Aerospace Corporation. The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 specifies that countries retain ownership of space artifacts, implying that Russia will maintain ownership over any recovered debris. This ongoing situation highlights the pressing need for improved practices in space debris mitigation, ensuring that future generations do not face the risks posed by abandoned or failing spacecraft.

In a broader sense, the upcoming reentry of Cosmos 482 serves as a powerful testament to the long-lasting impact of space exploration, showcasing how the remnants of past missions can have tangible implications today. This incident underscores the importance of proactive measures in the space community to address the challenges and dangers of space debris, ultimately guiding the future of space exploration.