The intersection of technology and governance is becoming increasingly relevant, and one of the recent developments in this area has raised both eyebrows and expectations. The UK government is set to introduce a new suite of tools powered by artificial intelligence (AI) that will assist civil servants in their day-to-day responsibilities. This initiative is particularly noteworthy due to its naming convention, as the AI assistant will be dubbed “Humphrey,” after the infamous character Sir Humphrey Appleby from the beloved sitcom “Yes, Minister.”

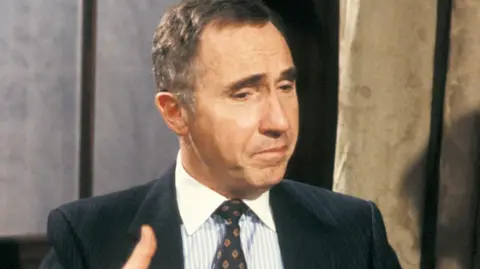

The show, which aired in the 1980s, featured Sir Humphrey as a crafty and often manipulative civil servant, known for his ability to navigate the murky waters of politics with an air of consummate control. By naming the AI tool after such a character, the government may be sending mixed signals regarding their commitment to transparency and accountability in public service. The officials behind this initiative argue that the assistant will “speed up the work of civil servants” and help save taxpayer money by minimizing the need for expensive consulting services.

However, this decision to draw from a character often perceived as “devious and controlling” is not without its critics. Tim Flagg, the chief operating officer of the trade body UKAI, expressed concerns that the choice of name could be detrimental to the government’s mission of embracing modern technology. According to Flagg, naming this AI tool after a Machiavellian personality might lead the public to distrust its intentions. He pointed out that such a name could alienate those outside the central offices of Whitehall, making it seem as though the AI will not be a tool of empowerment but rather one of manipulation.

On the day of the announcement, Peter Kyle, the Science and Technology Secretary, is expected to unveil other digital tools, which will include applications aimed at digitizing government documentation. These tools are part of a broader initiative to overhaul digital services in government, following the government’s recent AI Opportunities Action Plan. This plan reflects a growing recognition of the potential that AI technologies hold for enhancing efficiency within governmental operations.

The tools included in the “Humphrey” suite are primarily generative AI models designed to analyze and summarize large quantities of information. For instance, one of the applications, named “Consult,” aims to streamline the process of summarizing public responses to government inquiries. This task is currently performed by expensive external consultants, costing taxpayers around £100,000 with each iteration. Another tool, known as “Parlex,” serves to assist policymakers in sifting through previous parliamentary debates, which has the added benefit of anticipating potential political fallout from decisions made.

As part of this revolutionary endeavor, the government is also committed to improving data-sharing mechanisms between various departments, enhancing overall operational efficiency. While some critics may scoff at the naming decision, Flagg maintains optimism regarding the potential implemented technologies. He acknowledges the government possesses capable developers and expresses confidence that they will produce a useful product that will ultimately aid civil servants.

In conclusion, while the UK government’s initiative to integrate AI into public service may hold great potential, the naming choice of “Humphrey” serves as both a nod to popular culture and a source of skepticism. The duality of excitement and wariness surrounding this development underscores the challenges that accompany technological advancements in governance. As the tools become available, their effectiveness in empowering civil servants and improving public service delivery will likely be closely monitored and debated by stakeholders across the spectrum. Whether “Humphrey” will live up to its namesake in terms of intelligence or ultimately reinforce negative connotations remains to be seen.