A recent research initiative in China has taken an innovative approach to safeguarding the critically endangered Yangtze finless porpoise by delving into the rich literary heritage of ancient Chinese poetry. The study team meticulously examined over 700 poems dating from the Tang to the Qing dynasties, searching for references to the Yangtze finless porpoise. This endeavor aimed to uncover historical sightings and habitats of the species, as there remains limited information concerning its population history.

The Yangtze finless porpoise, recognized as the only freshwater porpoise in the world, has suffered drastic declines in its population over the last four decades. Today, estimates suggest there are fewer than 1,300 individuals remaining in the wild. In an effort to reverse this trend, researchers in eastern China have made substantial strides to understand the historical distribution of the porpoise, which will serve as a cornerstone for future conservation initiatives.

The research team’s findings highlighted dramatic alterations in the porpoise’s distribution, indicating a staggering 65% reduction in its historic range over the past 1,200 years. The most significant declines have been observed in the past century, a trend documented in a study published in the journal *Current Biology*. This stark reduction has raised alarm among scientists, with study coauthor Zhigang Mei sharing insights from local fishers who expressed that porpoises were once commonly seen in areas that now experience their complete absence. Such reflections prompted curiosity regarding the species’ historical habitats.

The Yangtze finless porpoise inhabits only the middle and lower regions of the Yangtze River basin in eastern China. Significant population drops—estimated at 60% from the early 1980s to the 2010s—have been attributed to a combination of illegal fishing, industrial pollution, dam constructions, and sand mining operations in connected lakes. Despite existing data from recent decades, scientists face a challenge termed “shifting baseline syndrome,” which limits their understanding of the porpoise’s original habitat.

The research efforts have generated pressing inquiries regarding the foundational components of a healthy population, essential for setting realistic conservation goals. As Mei mentioned, without understanding historical baselines, future generations may settle for ever-declining conditions being perceived as the ‘new normal’. Thus, the study sought to pose questions that could lead to actionable conservation strategies.

When traditional documentation sources offered little regarding the porpoise, the research team turned to literature for clues to the animal’s past. Surprising results emerged as they found little mention of porpoises in local chronicles, which instead focused on terrestrial animals marked by notable human interactions. In contrast, the elusive nature of the porpoise likely contributed to its absence in these records. Most historical sightings stemmed from local fishermen or curious travelers aboard boats navigating the Yangtze River—not from formal scientific documentation.

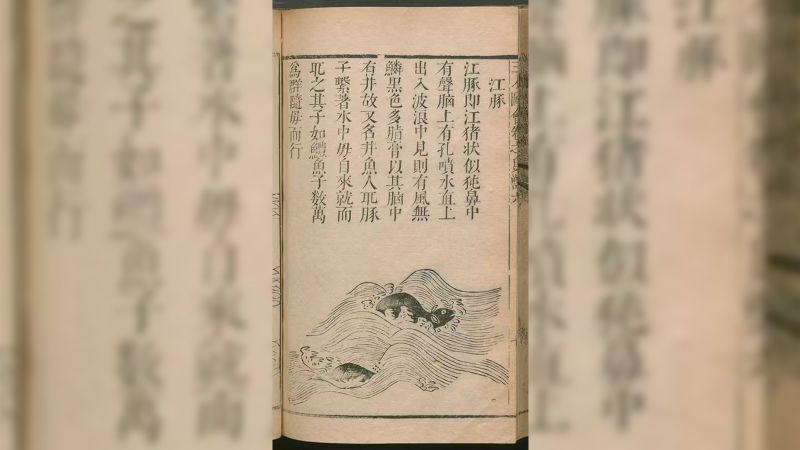

Upon realizing that ancient poetry could hold valuable data, the researchers undertook an extensive investigation of historical texts. This exploration led them through hundreds of poems dating back to 830 AD that referenced porpoises, focusing on geographical indicators and temporal contexts to precisely validate each poet’s observations. Approximately half of the poems provided detailed locality references, enabling researchers to track sightings throughout different dynasties.

Ancient Chinese poetry is renowned for its narrative potency, often showcasing personal experiences and observations of natural phenomena, making these literary works a useful metric for historical sightings of Yangtze finless porpoises. For example, a notable Qing Dynasty poem by Gu Silì encapsulated the mystical beauty of the river, emphasizing the porpoises’ connection to its environment. Critics have praised this unconventional research methodology, highlighting its success in translating simple textual data into significant ecological insights.

Employing history in wildlife research is not an entirely nuevos concept, typically applying more prominently in fields such as paleontology or archaeology. Yet, challenges remain, particularly regarding the reliability of observations from varied sources. Thus, researchers must fully investigate each poet’s background, evaluating travel histories and educational qualifications to ascertain the credibility of their accounts.

The Yangtze finless porpoise is marked by its distinct physical characteristics—a short snout, dark gray color, and absence of a dorsal fin—differentiating it visually from dolphins. As a mammal, it necessitates surfacing for air, making it visible to human observers. Yet, their lack of cultural significance historically limited their representation in literary depictions. The study does note a risk of confusion between references to the now-extinct baiji, a larger and lighter-colored dolphin, and the finless porpoise.

The ongoing extinction of the baiji serves as a cautionary tale for conservationists working to protect the Yangtze finless porpoise. As a crucial apex predator, the finless porpoise maintains ecological balance by feeding on fish and contributing to nutrient cycling processes through its migratory behavior.

These findings now provide scientists with a more robust understanding of the historical distribution of the finless porpoise