In the intricate tapestry of human evolution, a recently proposed species, Homo juluensis, has emerged from the shadows of confusion, bringing with it a sense of urgency and curiosity that grips scientists worldwide. This potential species is suggested based on a cache of ancient human-like fossils discovered in China, which have eluded precise classification for decades. Among the leading proponents of this theory are Christopher Bae, an anthropology professor from the University of Hawaii at Manoa, and Wu Xiujie, a senior professor at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing. Their work reignites a debate surrounding the complexity of our ancestral lineage, particularly in regard to species that lived between 100,000 and 300,000 years ago.

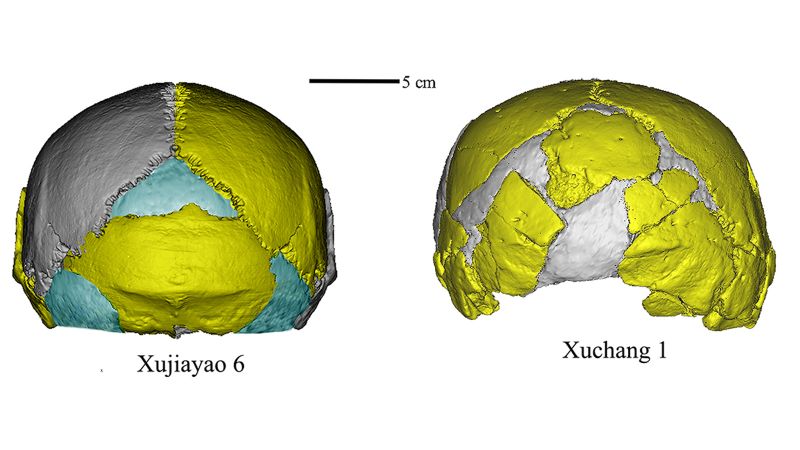

The fossils in question, primarily skull fragments, teeth, and jaws unearthed from various key archaeological sites including the Xujiayao site on the northern China border, exhibit extraordinarily large cranial capacities, estimated to be between 1,700 to 1,800 cubic centimeters. This astonishing size surpasses that of modern humans, Homo sapiens, whose average cranial capacity hovers around 1,450 cubic centimeters. Bae and Wu’s assertion that these fossils should be designated as a new species, Homo juluensis—which translates to “huge head” in Chinese—challenges long-held beliefs in paleoanthropology and invites scrutiny from their peers in the field.

Despite the provocative nature of their proposal, skepticism remains. Some experts argue that the classification of these fossils into a new species is premature due to insufficient comparative data, particularly regarding genetic analysis, which has become a cornerstone in modern taxonomy. Opponents, including paleoanthropologist Ryan McCrae from the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, stress that without a substantial comparison of the cranial remains to recognized Denisovan fossils, which have only been identified through genetic material rather than robust skeletals, it is risky to impose a new taxonomic label.

Compounding this debate is the controversial history of the multiregional model of human evolution, which suggested that archaic hominins evolved distinctly in various regions, including Asia. This perspective has largely lost favor in light of a growing body of evidence supporting the “Out of Africa” theory, positing that all modern humans descend from a common ancestral group that migrated out of Africa around 60,000 years ago. The fossils from Xujiayao and other sites in China are vital to understanding the diverse pathways of hominin evolution, particularly given the recent identification of fossils like the enigmatic Dragon Man, whose morphological attributes may overlap with those of the Xujiayao remains.

The Xujiayao specimens, alongside others discovered in various parts of China—such as the partial craniums in Henan province and a well-plucked skull resurfacing in Harbin—pose critical questions about the complex web of ancient human species that once roamed the Earth. This dynamic biogeography suggests that human evolution is far from a linear progression, and recent studies advocate for a thorough re-examination of Asian fossil finds. It is widely considered plausible that multiple hominin lineages coexisted in Asia during the Pleistocene epoch.

As researchers continue to comb through the ancient remains and re-evaluate historical classifications, the scientific community remains divided. The tension between accepting a new species designation versus maintaining older classifications reflects not only a battle over fossils but also over scientific narratives that shape our understanding of human origins. Moreover, the international ramifications of nomenclature decisions further complicate these discussions. While Bae and Wu have positioned Homo juluensis as a legitimate classification, it complicates the current status quo regarding the recognition and naming conventions for ancient human species.

As this debate unfolds, the exemplary situation continually illustrates the dynamic nature of scientific inquiry. Fossils are not merely relics buried in the ground—they are integral pieces to understanding our past. Each discovery brings questions, significance, and opportunities for reinterpretation. Thus, the investigation of Homo juluensis, while rooted deeply in the complexities of paleontology and genetic research, highlights a broader quest to unearth the enigma of human identity and our place within the evolutionary landscape.