The recent resurgence of an ancient writing system from Africa is challenging longstanding misconceptions about literacy on the continent. A wooden toolbox inscribed with this ancient script from Zambia has gone viral on social media, igniting conversations about the rich and overlooked history of African societies. Samba Yonga, one of the founders of the Women’s History Museum of Zambia, poignantly remarked, “We’ve grown up being told that Africans didn’t know how to read and write.” This sentiment underscores a prevalent misperception that has historically marginalized the intellectual traditions of various African cultures.

Yonga emphasizes the significance of this toolbox, stating that it serves as a catalyst for awakening the understanding of pre-colonial knowledge systems among women, a segment that was essential to societal structures. The toolbox is not merely an artefact; it symbolizes a cultural legacy of communication and knowledge that has been sidelined by colonial narratives. The museum’s initiative aims to highlight the role of women in historical communities, emphasizing how they have been integral in preserving cultural heritages, which have often been diminished following colonial encounters.

In addition to the toolbox, an intricately designed leather cloak adds depth to this narrative. Not seen in Zambia for over a century, its discovery signifies the wealth of history that remains untapped. Yonga states, “These artefacts signify a history that matters – and one that is largely unknown.” This cloak, like the toolbox, represents the vital role women played in both the domestic and communal spheres, a relationship that has been disrupted by colonial experiences.

Yonga and her colleague Mulenga Kapwepwe have been instrumental in exploring various artefacts collected during the colonial era, many of which remain undiscovered in museums worldwide. During a research trip to Sweden, they uncovered significant Zambian artefacts in the National Museums of World Cultures. Many of these items were collected over a hundred years ago by Swedish explorers and are housed in the museum, with Yonga expressing both astonishment and concern at the time those artefacts spent in silence while African knowledge systems weakened.

Among the most intriguing discoveries is the ancient writing system known as Sona, or Tusona, prevalent among the Chokwe, Luchazi, and Luvale peoples. This sophisticated form of communication utilized geometric patterns inscribed in various materials, from cloth to the skin. The symbols embody complex mathematical concepts and connections to nature, underscoring an intricate understanding of community life that coexisted with artistic expression. It is noteworthy that the original custodians of this knowledge were predominantly women, whose contributions historically remain underappreciated.

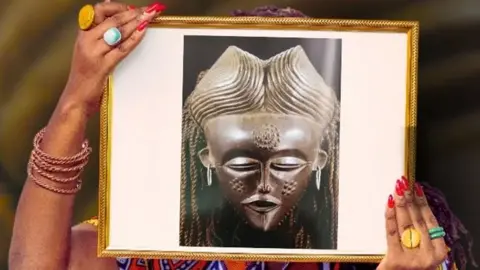

The campaign, dubbed the “Frame project,” utilizes social media to challenge the prevalent notions that African societies lacked their knowledge systems. It features striking images of cultural objects alongside explanations of their significance. Notably, the initiative exposes the systematic erasure of women’s roles in these societies, aiming to restore this vital aspect of their history.

A remarkable insight emerged during field research when Yonga and Kapwepwe discovered the importance of a seemingly mundane kitchen tool — a grinding stone. This object had significance beyond its utilitarian purpose, serving as a tombstone for the woman who owned it, honoring her contributions to the community’s food security. Yonga articulates, “What might look like just a grinding stone is in fact a symbol of women’s power.”

The establishment of the Women’s History Museum of Zambia in 2016 reflects a dedicated effort to document women’s histories and indigenous knowledge. Their work acts as a bridge to uncovering and preserving the unrecognized narratives that shape contemporary understanding of Zambian culture. Like a treasure hunt, they piece together fragmented histories to give voice to those who contributed to society yet have often been rendered invisible.

In recounting her journey, Yonga expresses a profound personal transformation. Gaining insight into her community’s history has deepened her understanding of her identity within the context of society. The impact of the Frame project echoes this sentiment, igniting a broader quest among many to connect with their heritage and reclaim their narratives, creating a future that acknowledges the legacies of the past.