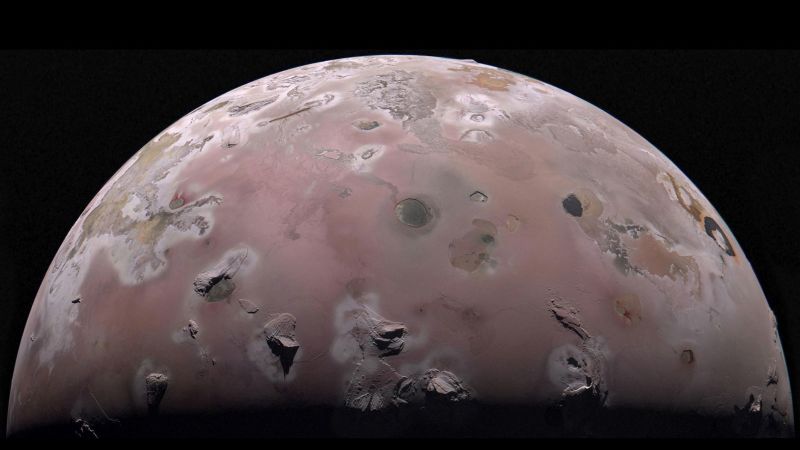

NASA’s Juno spacecraft, which has been diligently orbiting Jupiter since July 2016, has made significant progress in unraveling the enigma behind Io, one of Jupiter’s most extraordinary moons. Known for being the most volcanically active body in our solar system, Io’s fiery nature is under scrutiny through Juno’s recent flybys conducted in December 2023 and February. During these flybys, Juno approached as close as 930 miles (1,500 kilometers) to Io’s surface, capturing intricate images and critical data that contribute to a greater understanding of this tumultuous moon.

In many ways, Io can be compared in size to Earth’s moon, but its surface features are vastly different. Estimates suggest that Io is home to around 400 volcanoes that continuously erupt, releasing plumes and lava that cover the surface. Recently, researchers, during a presentation at the American Geophysical Union’s annual meeting in Washington, DC, shared insights from their analysis of the valuable data gathered during Juno’s flybys. Additionally, a comprehensive paper detailing these findings was published in the journal Nature.

Scott Bolton, co-author of the research and Juno’s principal investigator at the Southwest Research Institute, reflects on the fascinating characteristics of Io. “Io is one of the most intriguing objects in the whole solar system,” Bolton explains. The extensive volcanic activity is not just limited to a few regions but is pervasive across the entire moon, raising vital questions about the underlying mechanisms powering these eruptions.

One of the most groundbreaking revelations from the new data suggests that the multitude of volcanoes on Io could be fueled by separate chambers of hot magma rather than a single global ocean of magma beneath its surface—which had been a prevailing hypothesis. This could radically alter astronomers’ understanding of planetary geology and the processes that govern moons with subsurface oceans, particularly for other celestial bodies such as Jupiter’s moon Europa and exoplanets located in distant solar systems.

Diving into the history of Io, it was Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei who first discovered the moon on January 8, 1610. However, it wasn’t until the Voyager 1 spacecraft flew by Jupiter and its moons in 1979 that the wild volcanic activities on Io’s surface came to light. Linda Morabito, an imaging scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, is credited with this discovery, identifying a volcanic plume in Io’s imagery, a revelation that ignited decades of inquiry concerning the moon’s continuous volcanic activity.

Since that moment, planetary scientists, including Bolton, have sought to understand the sources feeding these violent eruptions. The relationship between Io and its parent planet, Jupiter, is critical to understanding the mechanics at play. Io’s orbit around the massive planet is irregular, compelling it to sometimes stray closer and at other times venture farther away. Completing a single orbit approximately every 42.5 hours, Io experiences tidal flexing, where Jupiter’s gravitational forces exert immense pressure on the moon, generating internal heat.

Bolton provides a vivid description of this process: “That’s what’s happening inside Io.” This squeezing effect generates significant heat, and when the temperatures rise sufficiently, Io’s insides are rendered molten, resulting in constant eruptions that resemble a never-ending rainfall of lava. The abundant energy from tidal flexing could potentially melt parts of Io’s interior, which, if extensive enough, would typically result in the formation of a global magma ocean detectable by Juno’s sophisticated instruments.

However, the data gathered by Juno does not support the existence of a global magma ocean beneath Io; instead, the findings present a picture of a rigid, mostly solid crust with localized pockets of magma fueling the volcanoes. This challenges the long-held theories and solves a 45-year-old mystery first posited by Voyager 1’s observations.

Lead study author Ryan Park reinforces the significance of these new discoveries, emphasizing their broader implications on our understanding of not just Io’s interior but also other celestial bodies, such as Saturn’s moon Enceladus, and even exoplanets beyond our solar system.

Juno’s ongoing mission continues to provide new insights into the dynamics of Jupiter and its moons. Recently, it completed a flyby over Jupiter’s cloud tops, and it plans to swing by the planet’s center on December 27, now having logged over 645.7 million miles (1.04 billion kilometers) since its mission commenced eight years ago. As the Juno mission progresses, it not only enhances our scientific knowledge of our solar system but also paints a vivid image of the primordial landscapes that characterize celestial bodies like Io, giving researchers a unique opportunity to study planetary formation and evolution on an unprecedented level.