NASA has recently celebrated a significant achievement concerning its Voyager 1 probe. After a prolonged communication blackout triggered by dwindling power levels, the engineers were able to restore contact, confirming that the spacecraft is functioning normally again. Having ventured into uncharted regions of space, Voyager 1 operates at an astonishing distance of approximately 15.4 billion miles (or 24.9 billion kilometers) from Earth. This feat highlights the remarkable resilience and ingenuity of the mission team, who have been navigating an array of challenges as they strive to maintain communication with this aging spacecraft.

The communication issues originated in October when Voyager 1 automatically shifted from its primary X-band radio transmitter to a less powerful S-band radio transmitter. This occurred following a command from the mission team on Earth to activate a heater on board, leading to a substantial power draw that required the spacecraft’s systems to adjust accordingly to conserve energy. Notably, this adjustment resulted in a near month-long blackout, during which time engineers were unable to receive any status updates or gather scientific data from the probe’s instruments.

In the face of this obstacle, NASA’s team undertook an impressive problem-solving initiative. After successfully commanding Voyager 1 to revert to its original X-band transmitter, they resumed data retrieval by mid-November. Kareem Badaruddin, the Voyager mission manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, noted that operating the probes in such an unpredictable fashion, given their age, is a learning experience for the team. Despite these trials, the engineers were pleased that they managed to recover from the issue while also gaining critical insights about the aging spacecraft.

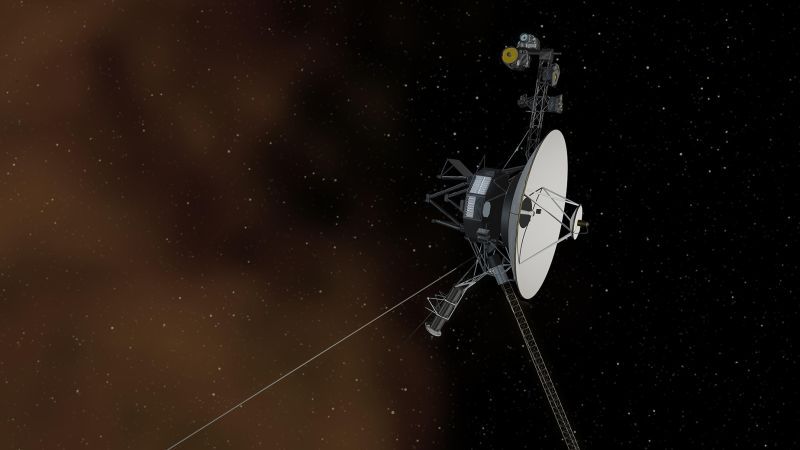

The Voyager probes, launched in 1977, were originally intended for a four-year mission to explore the largest planets within our solar system. Over the past 47 years, however, both probes have far outlasted their primary objectives, venturing into the interstellar realm and becoming the only spacecraft to operate beyond the heliosphere—a vast bubble of charged particles and magnetic fields that extends beyond Pluto’s orbit. Each probe derives power from decaying plutonium, losing approximately four watts annually—a rate of power depletion comparable to that of a standard energy-efficient light bulb.

According to Badaruddin, Voyager 2’s science instruments had to be powered down this year due to power constraints, but the longevity of both probes has surpassed all expectations. The mission team has made a concerted effort to conserve energy by disabling non-essential systems over the last five years, while to their surprise, the scientific instruments have continued to operate even at temperatures lower than those previously tested.

Engineers periodically command Voyager 1 to activate heaters to reverse radiation damage that has accumulated over decades. The latest incident arose when a command sent on October 16 prompted the spacecraft’s fault protection system to engage automatically, shutting down the X-band transmitter and swapping to the less power-hungry S-band transmitter, which hadn’t been utilized since 1981. This transition complicated communication until the team successfully identified the faint S-band signal and restored contact.

The recovery effort continued and culminated with the team commanding Voyager 1 to switch back to the X-band on November 7, enabling the collection of scientific data the following week. This instance is just one of several innovative strategies deployed by NASA engineers to navigate communication complexities since the probes were launched. Even as the mission team employs computer models to project power usage, the triggering of the fault protection system underscores the heightened uncertainty surrounding the spacecraft’s operational future.

As each Voyager probe began with ten scientific instruments, years have seen a reduction to only four instruments per spacecraft, which are now utilized to study plasma, magnetic fields, and particles in the intriguing domain of interstellar space. Continuous data acquisition is facilitated through the Deep Space Network, which comprises radio antennae spread across Earth. Unfortunately, the lack of onboard data storage means that during the communication outage, any scientific data sent home was inevitably lost.

In concluding reflections on the current state of the Voyager mission, Badaruddin observed that the primary concern lies in the sustainability of the science instruments rather than temporary data dropouts. With growing uncertainties regarding power distribution and instrument operation, the team remains steadfast in their efforts to extract every possible ounce of data and insight from these legendary probes.